People often ask me where I get my ideas.

It’s a very good question. Without ideas, lots of them, a novelist has nothing to say. The answer is: from absolutely everywhere. A chance conversation in the street with a total stranger. Reading an intriguing story in a newspaper. A sudden memory. A birthday party.

Reading other people’s work.

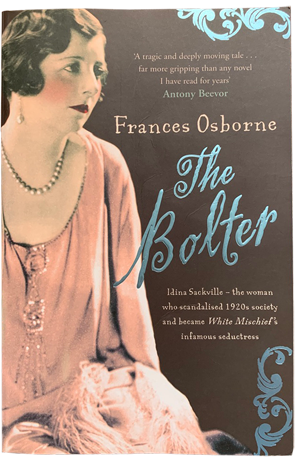

I first started writing Beatrice and Alexander in 2008 after reading The Bolter by Frances Osborne, a biography of Idina Sackville. Idina scandalised 1920s society and became an infamous seductress. Published by Virago in 2008, it’s an enthralling account of a dazzling but bitterly troubled life.

The book started me thinking about the three different types of women: those for whom family is everything in the world; those who have children they don’t really care about; and those who long to have children of their own, but remain barren.

My novel is set in 1911 when there were no tried and tested fertility treatments. The stigma that hung over women who married but failed to conceive was monumental. It blighted their entire lives.

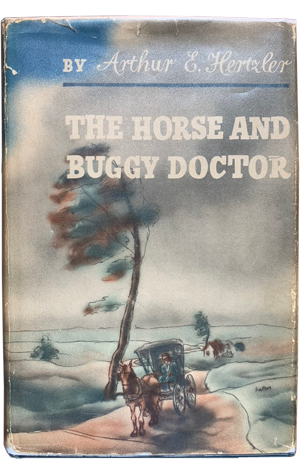

My thread of research led me to a second book, The Horse and Buggy Doctor, by Arthur E. Hertzler, M.D., published in 1938 by Harper & Brothers, New York & London. It’s the most brilliant memoir I’ve ever read of a long life spent in medicine. The illustration on the jacket and the few inside the book (which aren’t credited, sadly) are at the core of Beatrice and Alexander. In their honour I’ve called my hero Alexander Hertzler, and it’s his American story – if only a small part of it – that lies at the heart of my own invention.

I’m an author who likes to do her own research. Many writers have large teams of people buzzing around them, gathering facts, figures and all else besides. I like to stomp off on my own, often checking every blade of grass and counting the lamp posts, partly because you never know what you might find. But the early and late sections of Beatrice and Alexander take place in New York. I knew there was no way I could get there and start stomping. In 2003 I returned from a trip to New York with an early brand of the Covid virus. It very nearly killed me. I decided that air travel was no longer for me.

So, through an Agent I had at the time, I found the most brilliant American researcher, Kelly McMasters (kellyinbrooklyn@gmail.com). Kelly knows New York like the back of her hand. She read my complicated brief and understood immediately what I needed. Maps of the city in 1911, details of the then hospitals, records of medical training, what people swallowed when they felt ill: you name it, I needed it. For three months Kelly beavered away, sending me chunks of information she had patiently found and xeroxed on my behalf. And then more: stuff she thought I might need. That is the mark of the true researcher. They follow their thread in case it might lead somewhere useful. Kelly went beyond my brief, giving me ideas I would not have had without her. I cannot thank her enough for all her help.

Twelve years is a long time to keep ideas for a storyline alive and fresh. Other projects kept getting in the way. But my Beatrice and Alexander characters wouldn’t leave me alone. By 2019 I had four different versions on my computer. I decided enough was enough. Do or die. I must either knuckle under and confront all four versions head on, or give up on the project and wipe the dusty, jumbled indecisive slate clean.

The reason I’d stalled at exactly the same point in all four versions quickly became obvious. Some of the novel is crucially set in Charlbury, Oxfordshire, and involves horses. Although I knew and loved the little town, I couldn’t find an exact spot to place my Davenports. And although I can admire horses enough to smile and stroke, if you were to put me on one, I should fall off faster than you could say Dobbin.

And then something quite miraculous happened.

One summer morning on Monday 1 July 2019, I caught the bus from Woodstock to Charlbury to begin stomping around, trying to find an exact location. As I was wandering backwards up a hill in a vague early-morning stupor, I bumped into an old friend. Nobody who wanders around like that in Charlbury goes unchallenged for long. I told her what I was looking for.

“You need to talk to Sally,” I was told. “She’s great. She’s our Vicar. She lives the other side of the Church.”

Within the space of ten minutes, I was in the Church, and walking around it with a mounting sense of excitement. On Monday 8 July, the Reverend Dr Sally Welch of St Mary’s Charlbury was kind enough to let me walk into her back garden. It is extraordinary. The Old Rectory next door still has its stables. Tears of relief and joy filled my eyes. I had my exact spot. I had my stables. I had the sloping garden, the exact place of the river, the railway line and so much more.

Now all I needed was An Horse or Two. Or preferably Three. Not to ride away on, no siree. Just to admire from close up. I don’t own a car. I couldn’t afford to trail around the countryside looking for a set of stables that would probably be closed when I arrived.

But suddenly, there was Millie Coles, the marvellous Groom at Park Estate in Blenheim. On Tuesday 16 July 2019, in the blazing heat, I spent a glorious hour admiring Millie’s steeds. Domino with her swirling coat of black, white and orange, now has pride of place in Beatrice and Alexander. I was allowed to stroke her. To look into her all-too-perceptive eyes. To see the cleanness of the sawdust on the ground the horses pawed. To hear their silent watchfulness. To become a part for a few moments of their utterly magical world.

So once again, here I am thanking Blenheim – and this time in particular my Millie – for the love, dedication and care that go into her work, and made mine possible.

The horses and the heat and the gratitude had fair worn me out. Millie spotted I was flagging. She drove me back to the Palace. I sat down with a coffee in The Blenheim Pantry – a perfect space to write a best-seller – and then hopped, skipped and jumped back to my desk.

By Friday 4 October 2019 I had polished the first 80 pages of Beatrice and Alexander and written a full synopsis of the remainder of the story. I set myself a deadline to complete the novel by the end of 2019. And I did it, with tremendous zest and enthusiasm. When field research works as well as this, it can be a novelist’s inspiration. Perhaps I should send Domino a year’s supply of carrots with my name on them. In fact, that’s the best idea I’ve had all day.

Domino, here I come.

New York in 1911: Image from YouTube by Denis Shiryaev: a remarkable new colouration of what life was like while Alexander Hertzler lived there

Stone arch bridge in Hampstead Heath, London