“Tobias Mellwood ran as fast as the burning sand would allow, down the beach towards the lazy edges of the sea. Sweat poured into his eyes. The relentless noonday sun dominated the sweltering cloudless sky.”

The opening of my next novel? Possibly.

A lesson in how to “show don’t tell”? Yes, exactly that.

There are very few absolute rules in the world of the novelist. Don’t merely tell me that “It was a very hot day.” Show me. Give me specific details. Make me feel the heat. Only then will I start to feel concern for Tobias who might just be running away from his maniac of a brother or celebrating the fact that he has finally learned to swim.

One of the other rules is: There are no ideas but in things.

Of course the well-told story centres on its characters, its plot, its complicated storyline, its needing to make the reader desperate to turn the next page, and then the next.

But our lives are dominated by the things we have around us. Our breakfast toast and marmalade, our jeans and trainers, our huts, igloos and bungalows, our window boxes, our shopping baskets, our tambourines. The novelist must choose which ones to use and to what purpose. The storyline needs to be held together by a thread of things.

I describe my Memoir, Finding My Voice, as being like “a necklace of beads”: different shapes and colours, differing textures – rough, smooth, light or dark – held together by the plaited thread of time.

In the same way, any good storyline needs its objects: things the novelist selects from the thousands surrounding their lives to reveal the necklace of their story.

Tiny thimbles will qualify. Who worked with them, wore them, and why? Feathers dropped from a fan outside a cabin door. Who sits waving the air with it? Detective Inspector Morse spent his life scrabbling around for clues. The smaller they became, the more beer he needed to answer the questions – but answer them he more than usually did. Poirot’s “little grey cells” were fired into life by handwriting on an ancient document, a hairline crack in a bottle, the stain of lipstick on a china cup.

In my latest novel, Beatrice and Alexander, a small lace handkerchief smelling of stale hyacinths suddenly becomes, for Beatrice, an humiliating insult she discovers in her husband’s smoking jacket. The thing is more than its embroidered lace. It is itself: but it is also what it stands for. Infidelity. Proof she never wanted to find now stares her in the face. Its set of initials mocks her. The square of linen has no name for her – but it must surely mean more than a sneeze to her husband.

In Daddy’s Girl, Eleanor Drummond has to clear her father’s studio after his sudden death. She finds a small brass key stuffed into an ancient leather purse. Why is it there? What might it unlock? In an ancient bureau she manages to find a bundle of love letters. Who are they from? And so the thread of discovery unravels its path to the truth.

We keep our readers guessing. We keep our beloved readers turning the next page. In my teenage novel, Coming of Age, I have used a faded postcard from Italy with its message of passionate love. In Lost and Found, the sleeve of a red sweater reveals two people hiding on a narrow boat. In The Drowning Jenna finds her younger brother’s diary. In Larkswood, Louisa discovers an old portrait of members of her family hidden in the attic. She puts two and two together and makes one hundred not out.

Of course, all this looks so easy. Believe me, it isn’t. You can’t just suddenly drop things however big or small into the plot at the last minute and hope they won’t sink like a stone. They can never be random second thoughts. They need to be built into the good firm storyline from the very beginning as one of its foundation stones that will stand the test of time.

Fail to prepare and you will only prepare to fail.

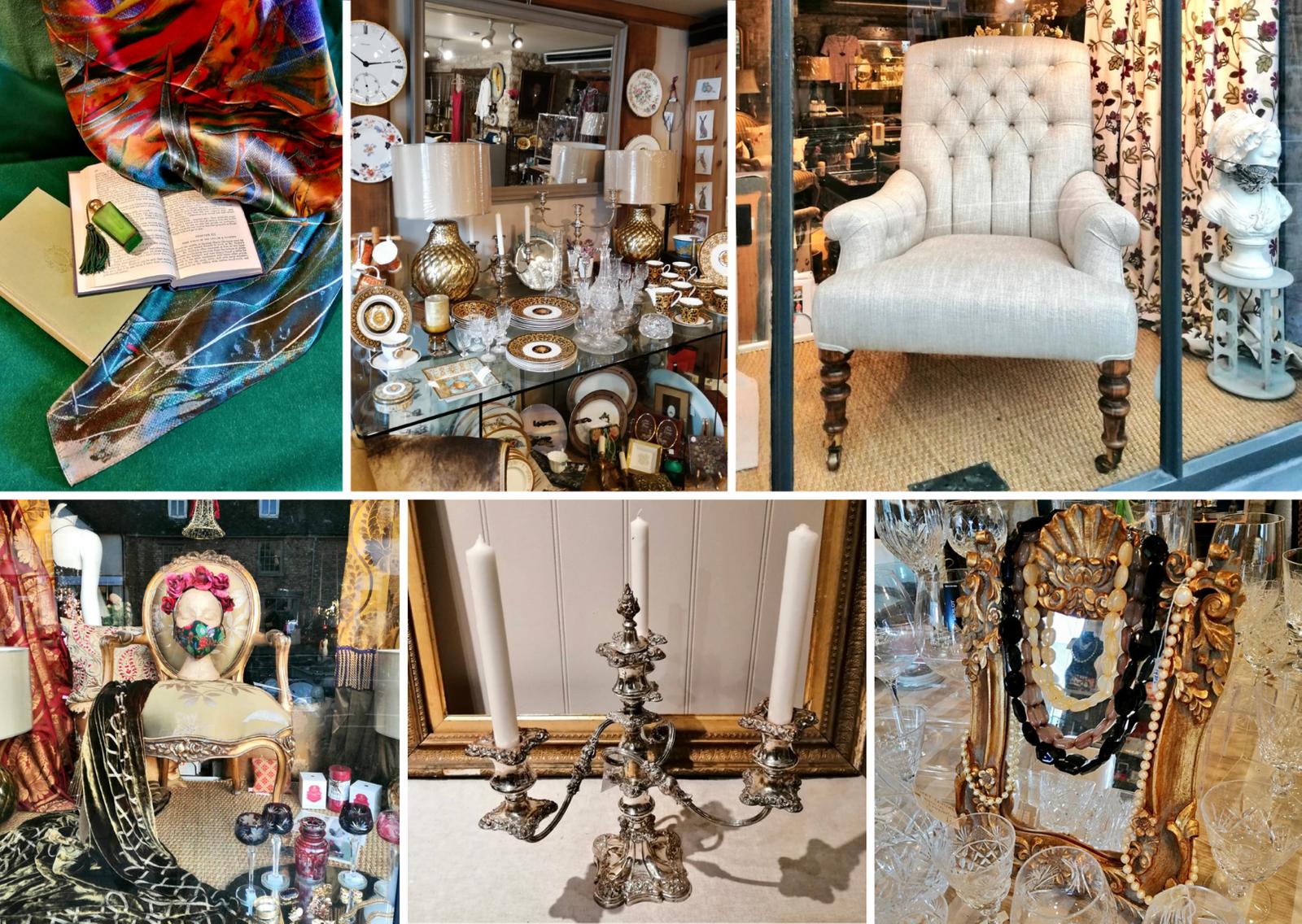

I have often browsed in one of Woodstock’s wonderful shops: Gleide’s Décor is a treasure trove of mixed delights: grist to the novelist’s mill, as varied and succulent as liquorice allsorts, and with a considerably longer life.

Here is my poem to her Aladdin’s Cave:

Gleide’s Décor of Delights

This paradise of ornaments caters for every taste –

This paradise of ornaments caters for every taste –

A luminosity of lamps, embroidered cushions laced

With silk and satin flowers, a dalliance of green:

A décor of a shop indeed, this paradise of gleam.

I spot a mirror – just my height – I stroke a velvet skirt:

This haven of a shop rebuffs our modern world of dirt.

Its chosen objects glisten, sitting with polished pride,

Speaking with timeless voices of a world that’s long since died.

This paradise of ornaments reveals every style:

Elaborate glass, a silver dish, a woven woollen pile

Of blankets for the frozen, of sweetness for the sour.

I choose to stand, to wander here, to spend a fragrant hour

Within this sanctuary of dreams. Outside the lorries fume

In here the quiet and the peace allows the curtained room

To offer chosen gatherings: unique, hand-picked, revealed.

I love them all. I’ll buy just one. We wrap. The bargain’s sealed.